“If I do it, can I play Xbox after?”

“Is everyone doing it?”

“Can you just do it since you’re better at it?”

So would begin the litany of questions when I assigned my sons even the most basic weekend chores. Whether charged with watering, dusting, or raking, the boys inevitably would whine, slump their shoulders and feign sudden, fretful bewilderment. “How do I know which plants need water?” “What’s a Swiffer?” “We have a shed?”

Truthfully, my children were not sparing me much labor by pitching in. I cannot count how many times I would stop what I was doing to liberate an area rug being swallowed by a vacuum or to rescue a vase perched a micrometer from a mantel’s edge. Still, I soldiered on, determined to instill in my kids a strong work ethic and a sense of responsibility. Each weekly outburst, though, stoked simmering doubts that my mission was succeeding.

Then one dreamlike Friday the tables turned.

My seven-year-old announced that he would need to finish his science fair project over the weekend. With a toothy smile, he turned from my husband to me and with complete sincerity asked, “Who wants to help me?” I waited for him to appreciate the irony.

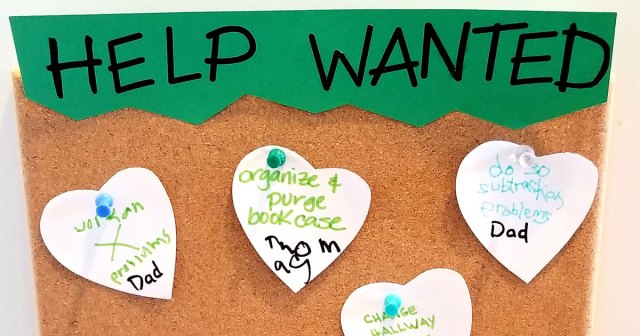

Though that night did not afford our family any lessons on paradoxes, it did produce our new favorite tool for a stress-free weekend: The “Help Wanted Bulletin Board.” Our family has found this device to be most valuable when used in the following way.

- The “Help Wanted Bulletin Board” is literally a bulletin board that hangs next to our refrigerator, the most visited spot in the house.

- Throughout the week, each member of the family takes a piece of paper, jots down a chore they anticipate may require assistance and pins it to the board. Each person posts two jobs in total.

- The activities must be reasonable in scope. Our family defines “reasonable” as any task that can be performed by any family member in one hour. Jobs have included cleaning out the toy chests, skimming the pool, practicing math facts, and weeding the back yard.

- All requests should be posted by Friday night.

- Although everyone peruses the job postings throughout the week, no one commits to any until Saturday morning. At that time, each member of the family signs their name onto two posted job requests. I have found that my boys have a greater sense of control and approach their responsibilities more eagerly when they can select their jobs. To that end, the adults choose last so that the kids have more tasks from which to pick.

- All jobs must be completed by early Sunday evening. The job solicitor and the job assistant decide together when they will work to complete the assignment.

- When a job is done, the posting is crossed out. I am still amused by how triumphant the boys look when they do this, but I also understand that the “x” is tangible proof of their success and a validation of their work.

- Finally, right before bedtime on Sunday night, we gather at the bulletin board and review what our family accomplished. Each job solicitor thanks his or her assistant, and it is impressive how much goodwill is fostered before our children retire for the evening.

Ending the weekend on a harmonious note is but one benefit of this approach to chores. Others have followed. With the board sitting in plain view every day, my sons understand that the weekend will bring housework. This visual reminder allows the boys to prepare mentally for chores. By eliminating any surprises, the board has reduced much of the whining in our house.

Though household duties are still inevitable, they no longer feel arbitrary. The board lets my children consider how they will contribute in the days ahead. They have developed a sense of ownership by having a say in what they do, and this autonomy has fostered pride in their work.

Each family member appreciates the support they receive while simultaneously feeling good about helping someone. There now exists a feeling of our family operating as a team. We enter the weekend knowing that someone has already offered to help us. What’s more, no one is shunted off to a corner of the house to work alone, as sometimes would happen before we used the board. Instead, each of us enjoys companionship while we work. More than once my kids have spontaneously offered up stories about what is happening at school while occupied with sweeping or washing dishes beside me. For me, these unprompted talks are the happiest consequence of the way we handle housework now.

My kids now take time to discern which of their own tasks they can do by themselves and which are best suited to a team effort. Subsequently, they have become more transparent about which responsibilities they find difficult and which they just do not want to do.

Finally, the “Help Wanted Bulletin Board” reinforces the notion that everyone needs help. Often children are told at school or at home that asking for help is not a flaw, but an asset exhibited by strong leaders. The “Help Wanted Bulletin Board” reinforces this sometimes-challenging idea. Each day it literally shows my boys that even the “oldest and wisest” can seek support and even the smallest and youngest can provide it.